Introduction

Apache Dubbo is a popular Java open-source, high-performance RPC (Remote Procedure Call) framework designed to simplify the development of microservices-based and distributed systems. Originally created by Alibaba, Dubbo has gained widespread popularity and is now maintained as a top-level Apache project with 40K stars on GitHub. At its core, Dubbo provides a robust communication protocol that allows services to seamlessly exchange data and invoke methods across different networked nodes, enabling the creation of scalable, flexible, and reliable applications. With its rich ecosystem and community support, Apache Dubbo has become a go-to choice for organizations seeking to harness the power of distributed computing in their software solutions.

In the past, several publications covered vulnerabilities in the framework, mainly affecting the provider end of the RPC layout, such as The 0xDABB of Doom. In 2021, Alvaro Muñoz published great research on the framework with an article named “Apache Dubbo: All roads lead to RCE“, disclosing more than a dozen RCE vulnerabilities.

Interestingly, Muñoz unveiled and discussed a bit on vulnerabilities affecting the consumer end rather than the provider (we will explain Dubbo’s architecture in the next section). The curiosity about this less researched side of Dubbo led us to unveil two other interesting findings that later were debatably not considered vulnerabilities by Apache. Nevertheless, we publish our research out of technical interest so that the community is aware of the risks. Following our disclosure, Apache updated its documentation to provide clearer safety instructions for users.

Key Information

- Sonar’s Vulnerability Research Team has discovered two security issues in Apache Dubbo.

- After reporting and discussing the findings, the Apache team didn’t classify them as vulnerabilities.

- Despite having similar issues being recognized as vulnerabilities in the past, the Apache team claimed that it is the user’s responsibility to make sure that registries are well protected as they should provide a shield against untrusted Providers.

- Following our notes on the unclarity of this point of view in their documentation, Apache updated its documentation for users to protect themselves better.

Impact

Apache Dubbo consumers who invoke RPC functions on untrusted provides or using non-secure registries are susceptible to arbitrary object deserialization, which can eventually result in remote code execution (RCE).

Apache Dubbo Technical Details

In this section, we will showcase the technical details and explanation of our findings. We will discuss the common Dubbo architecture and how this attack vector works.

Background

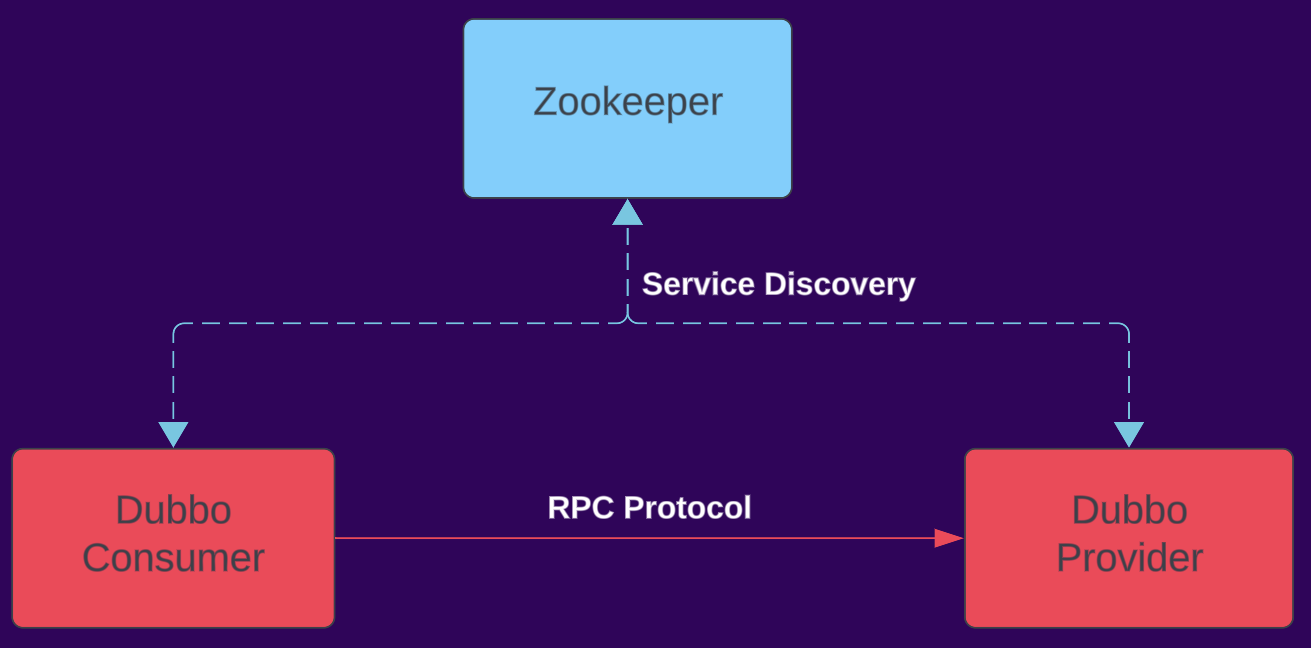

Apache Dubbo provides an RPC framework based on Java with three main components in the architecture:

- Provider - the “server” that exposes functions for execution.

- Consumer - the “client” that invokes predefined functions on the provider.

- Registry - Holds information for and from both consumers and providers (for example, when a consumer wants to invoke a function, they get the provider metadata, address, and more from the registry).

The basic code for a consumer is quite straightforward. At first, we set up a Dubbo reference service and name our application:

1 | ReferenceConfig<GreetingsService> reference = new ReferenceConfig<>(); |

After this, the reference is configured to a specific registry by calling setRegistry. This is a crucial step, as we will see later:

1 | reference.setRegistry(new RegistryConfig("multicast://224.5.6.7:1234")); |

Next, our desired interface will be set, which will result in Dubbo providing the relevant server that implements a corresponding function. At last, we can invoke a function on the provider and access the results:

1 | reference.setInterface(GreetingsService.class); |

In the past, there were multiple vulnerabilities, mainly affecting the providers. But as demonstrated before by Alvaro Muñoz (CVE-2021-30181, CVE-2021-30180, GHSL-2021-040, GHSL-2021-041, and GHSL-2021-042), vulnerabilities in consumers happened by poisoning the registry: “Zookeeper supports authentication but it is disabled by default and in most installations, and other systems such as Nacos do not even support authentication”

While previous attacks on consumers were by controlling configurations via the registry, this attack focuses on the response’s deserialization. A specifically crafted response on an invocation request might execute arbitrary code on the consumer.

An attacker can manipulate a consumer to invoke a function on a malicious provider in multiple ways such as:

- Creating a new malicious provider in the registry.

- Changing an existing provider address in the registry to an attacker-controlled one.

- Having previous control over a provider (lateral movement).

- Social engineering.

As discussed before, since registries don’t have authentication by default (some don’t support it at all), it is important to emphasize to users that this attacker scenario is feasible. As a result of our report, Apache clarified in the documentation its threat model, claiming that everything from the registry is considered trusted, users should enable authentication in their registries, and avoid exposing them to the public.

The code in the consumer that invokes a function on a provider will first check the supported provider’s serialization via the registry. Later, it will send the data (such as function parameters) serialized using the supported methods. Some serialization methods are considered safe (fastjson2, hessian2, …) and others are not (native-java, kyro, …). On the provider’s end, a check is made to see if the request’s data serialization is supported using a flag called SERIALIZATION_SECURITY_CHECK_KEY, which is true by default.

This prevents an attacker from using arbitrary serialization methods (a vulnerability found previously by Dor Tumarkin and Alvaro Munoz independently tracked as CVE-2021-25641).

Finding 1 - Arbitrary Object Deserialization via the Dubbo protocol

Despite having the same SERIALIZATION_SECURITY_CHECK_KEY flag on the consumer’s end, all it’s doing is checking that the response’s serialization type is the same as the one sent. Since this attack vector relies on an attacker-controlled provider, the supported serialization of the provider can also be modified to an unsafe one, causing the response deserialization to be unsafe.

A malicious provider can be registered with the prefer.serialization=nativejava parameter in the URL (in addition to decode.in.io.thread=true and corresponding to the registered consumer’s interface, version, etc. To ensure the desired function registration). This forces the consumer to use nativejava serialization when sending data to the provider, automatically allowing deserializing the response with the unsafe nativejava deserialization wrapper.

Let’s assume the following registration example:

1 | 'dubbo://192.168.1.20:20881/org.apache.dubbo.samples.api.GreetingsService?prefer.serialization=nativejava,fastjson2,hessian2&decode.in.io.thread=true&application=demo-provider&scopeModel=test&deprecated=false&dubbo=2.0.2&dynamic=true&generic=false&interface=org.apache.dubbo.samples.api.GreetingsService&methods=sayHi,sayHu&release=3.2.4&service-name-mapping=true&side=provider×tamp=' + str(int(time.time()*1000)).encode("utf-8") |

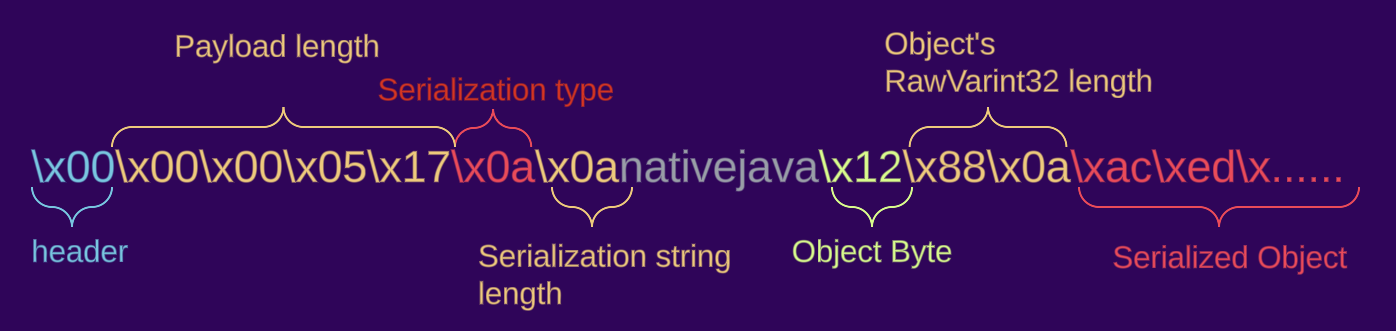

According to the Dubbo protocol, the malicious provider response header should look like this:

- Dubbo protocol header

\xda\xbb - Deserialization id

\x07(7 - for nativejava), - Response code

\x14(20 for successful invocation) - The following 8 bytes are the “future id” which are taken from the request.

- Serialized object length

- Serialized object

This header will result in the payload ending up in the vulnerable decode function call. Since Dubbo first reads a byte flag from the object and then deserializes accordingly, an attacker would need to start the object with a serialized byte (adding \x77\x01\x01 for flag 1, meaning no exception and an object without attachments).

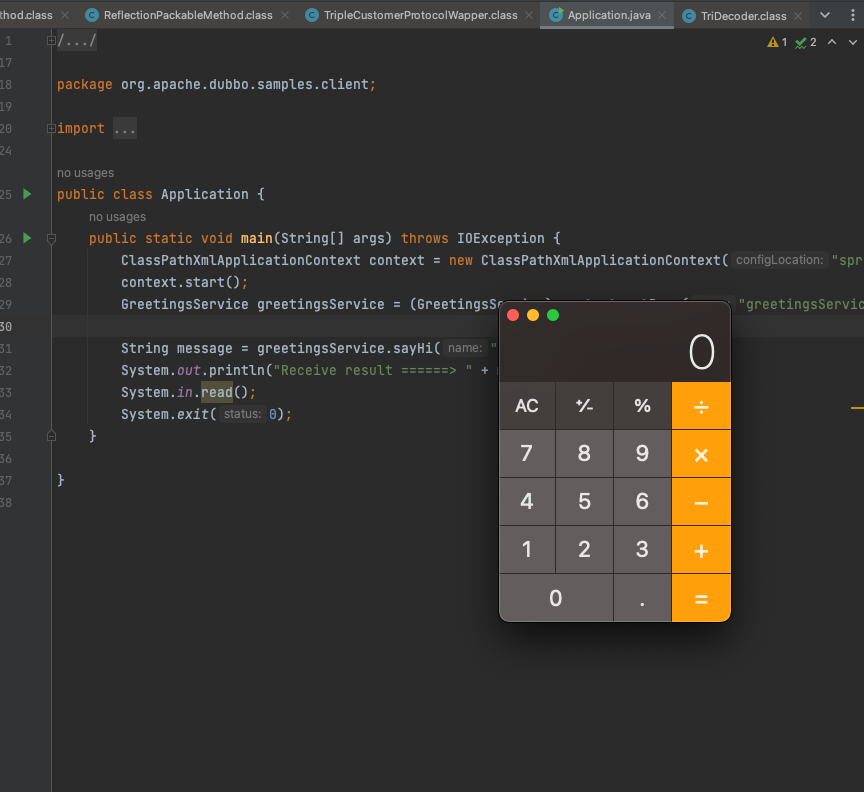

Using a deserialization gadget payload (for demonstration purposes, generated via ysoserial), a consumer that invokes a function on a malicious provider is susceptible to arbitrary code execution:

Finding 2 - Arbitrary Object Deserialization via Triple/gRPC protocol

Following the same attack surface as before, an attacker can register a provider using a different protocol than dubbo://. Consumers support the following protocols out of the box and don’t require any special changes to the code.

- registry:

org.apache.dubbo.registry.integration.InterfaceCompatibleRegistryProtocol - rest:

org.apache.dubbo.rpc.protocol.rest.RestProtocol - injvm:

org.apache.dubbo.rpc.protocol.injvm.InjvmProtocol - service-discovery-registry:

org.apache.dubbo.registry.integration.RegistryProtocol - mock:

org.apache.dubbo.rpc.support.MockProtocol - dubbo:

org.apache.dubbo.rpc.protocol.dubbo.DubboProtocol - tri:

org.apache.dubbo.rpc.protocol.tri.TripleProtocol - grpc:

org.apache.dubbo.rpc.protocol.tri.GrpcProtocol

According to the provider’s protocol registered in the registry, the consumer will use different data decoders/encoders. The tri and grpc protocols are susceptible to Arbitrary Object Deserialization when receiving a response, in a similar fashion to the first finding. Both protocols underline using HTTP2 and gRPC.

In the following example, a malicious provider is registered with the prefer.serialization=nativejava parameter in the URL but with the tri:// or grpc:// protocol (unlike dubbo:// scheme used by default in the first finding):

1 | 'tri://192.168.1.20:20881/org.apache.dubbo.samples.api.GreetingsService?prefer.serialization=nativejava,fastjson2,hessian2&release=3.2.4&application=demo-provider&scopeModel=test&deprecated=false&dubbo=2.0.2&dynamic=true&generic=false&interface=org.apache.dubbo.samples.api.GreetingsService&methods=sayHi,sayHu&service-name-mapping=true&side=provider&decode.in.io.thread=true×tamp=' + str(int(time.time()*1000)).encode("utf-8") |

The data received from the provider is decoded here (more specifically, the data frame). According to the deliver function and the parseFrom this is the data structure:

- Header byte (

\x00) - Length of following data,

- Serialization type byte (

\x0a) - Serialization type text length byte

- Serialization type text (

nativejava) - Object byte (

\x12) - Object length, calculated via protobuf’s RawVarint32

- Object payload

The vulnerable function unpacks and deserializes any data received from the provider if the deserialization type is included in the prefer.serialization parameter, which is controlled by the attacker.

Similarly to the first demonstration, a gadget payload generated via ysoserial would leverage the arbitrary object deserialization to execute arbitrary code on the consumer when invoking a function on a malicious provider.

Apache Response

After reporting our findings to Apache, they claimed that the risk of malicious providers or infiltration using an unprotected registry is introduced by the user. Following our communication explaining that this threat model was unclear to us and likely to users of the framework, Apache updated its documentation accordingly.

Timeline

| Date | Action |

|---|---|

| 2023-08-28 | We report all issues to the vendor. |

| 2023-09-29 | Vendor disputed the report claiming this attack is not considered in their threat model. |

| 2023-12-15 | After back-and-forth communication, the vendor agreed that their point of view was not conveyed through the documentation and updated it accordingly. |

Summary

This blog covered a different way of introducing security risks into an Apache Dubbo infrastructure. Despite it being disputed by the vendor, we are confident that our research helps contribute to the documentation and, alongside this publication, makes users aware of those risks.

This example showcased misinterpretation due to confusing flag verification. Additionally, it highlighted the absence of a well-defined threat model, which can bewilder users. At Sonar, we stress the significance of Clean Code as it enhances code readability, maintainability, and security. Clean Code promotes clear and concise code structures, making it easier for developers to identify potential vulnerabilities and implement appropriate security measures. By adhering to Clean Code principles, organizations can minimize the risk of security breaches and ensure the integrity of their software applications.